The Cardiology department and the Area of Cell Therapy of Cordoba hospital Reina Sofia are carrying out clinical tests with patients who have suffered from a severe heart attack. With the implantation of the patient's stem cells, the heart regenerates thus improving its wall motion, that is, its cardiac performance. Indeed for the last four years, the Area of Cell Therapy of Cordoba hospital, led by haematologist Dr. Concha Herrera, has been implementing a therapy program with adult stem cells in patients with heart-related problems. However, this therapy is not a service the hospital offers yet. More specifically, at the end of 2007 the hospital ended a clinical test with patients who had suffered a severe myocardial infarction, that is, an obstruction of one of the main coronary arteries that stops the blood pump to the heart.

The test consisted of treating 30 people split into three groups of ten each at random. The first group was the control group, where patients received standard treatment for acute myocardial infarction; the second group was treated with stem cells directly implanted into the coronary artery affected using a catheterization; the third group was treated with a medicine called G-CSF, which makes cells move from the marrow to the blood, so that they get to the heart in a natural way, without having to do so through a catheter.

At the end of the test, the results revealed that the two groups treated without cells improved slightly, whereas patients transplanted with stem cells through the coronary arteries (vessels which bring the blood to the Herat muscle) did improve their ventricular function much more. This was interpreted as a significant decrease of the cardiac failure symptoms such as pain, fatigue and breathlessness when making small efforts.

Moreover, with this process it is possible to prevent some acute arrhythmias (change or irregularity in the rhythm of the heartbeat), which in many cases could result in the patient's death. ‘However, it does not prevent a future heart attack', Dr. Herrera assures.

In short, the stem cells transplanted from the marrow into the heart muscle have a double function: on the one hand they regenerate the heart cells, the cardiomiocites. In addition to this, they segregate a series of proangiogenic factors that produce blood vessels (angiogenesis) and can also produce the recruitment of stem cells that are in the myocardium itself.

The Are of Cell Therapy, led by Dr. Herrera, is currently developing other trials in the cardiology department, both in patients with acute myocardial infarction (35) and in those with chronic ischemic cardiopathy, due to one or more heart attacks suffered in the past, either months or years ago (20 patients). Moreover, in the last few months a new clinical trial has been started - so far in eight patients- who suffer from a disease called Dilated Myocardiopathy. The origin of this disease is unknown but it causes a very severe cardiac failure which conditions the need for a heart transplant in many cases. So far, ‘the results in these first patients are very satisfactory'.

'We will start shortly a clinical test where we will use stem cells from the marrow in diabetic patients who have the artery taking the blood to the lower limbs blocked. This pathology, called peripheral ischemia, can result in a limb being amputated'.

This work, published in Revista Española de Cardiología journal, has been awarded with a prize by the Sociedad Española de Cardiología.

INTERNAL MEDICINE The internal medicine blog , where you can have details on alternatice medicine , latest trends in medicine , new drugs in the market , school of medicine etc

Stem Cells Transplanted From Marrow Into Heart May Improve Heart's Performance

Thursday, May 28, 2009 at 8:44 PM Posted by Sajith

Stronger Material For Filling Dental Cavities Has Ingredients From Human Body

Tuesday, May 26, 2009 at 11:44 PM Posted by Sajith

Scientists in Canada and China are reporting development of a new dental filling material that substitutes natural ingredients from the human body for controversial ingredients in existing "composite," or plastic, fillings. The new material appears stronger and longer lasting as well, with the potential for reducing painful filling cracks and emergency visits to the dentist, the scientists say. Julian X.X. Zhu and colleagues point out that dentists increasingly are using white fillings made from plastic, rather than "silver" dental fillings. Those traditional fillings contain mercury, which has raised health concerns among some consumers and environmental issues in its production. However, many plastic fillings contain controversial ingredients (such as BisGMA) linked to premature cracking of fillings and slowly release bisphenol A, a substance considered as potentially toxic to humans and to the environment.

The scientists developed a dental composite that does not contain these ingredients. Instead, it uses "bile acids," natural substances produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder that help digest fats. The researchers showed in laboratory studies that the bile acid-derived resins form a hard, durable plastic that resists cracking better than existing composites.

Brain-behavior Disconnect In Cocaine Addiction

at 11:35 PM Posted by Sajith

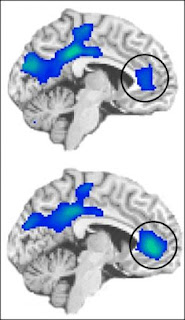

Parts of the brain involved in monitoring behaviors and emotions show different levels of activity in cocaine users relative to non-drug users, even when both groups perform equally well on a psychological test. These results — from a brain-imaging study conducted at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory and published online the week of May 25, 2009, by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences — suggest that such impairments may underlie addictive vulnerability, and that treatments aimed at improving these functions could help addicted individuals resist drugs."Many studies have found decreased brain activity in drug-addicted individuals relative to healthy control subjects during psychological tests," said lead author Rita Goldstein, a psychologist at Brookhaven Lab. "But it's never been clear if these differences were due to varying levels of interest or ability between the two groups. This is the first study to look at two groups matched for performance and interest — and we still see dramatic differences in the brain regions that play a very significant role in the ability to monitor behavior and regulate emotion, which are both important to resisting drug use.

"Whether these brain differences are an underlying cause or a consequence of addiction, the brain regions involved should be considered targets for new kinds of treatments aimed at improving function and self-regulatory control," Goldstein said.

The researchers studied 17 active cocaine users and 17 demographically matched healthy control subjects. Both groups were trained to push one of four colored buttons corresponding to the color of type used to present words that were either related to drug use (e.g., crack, addict) or neutral household terms. Subjects were given monetary rewards for fast, accurate performance — up to 50 cents for each correct answer on some tests, for a maximum of $75.

After training, both groups performed equally well on this same test while lying in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner, with performance improving when they knew they'd be earning the highest monetary reward. During the tests, the scientists used functional MRI (fMRI) to indirectly measure the amount of oxygen being used by specific regions of the brain, as an indicator of brain activity in those regions.

There were three main differences between the cocaine-addicted subjects and the healthy controls:

* The cocaine users had reduced activity in a portion of the anterior cingulate cortex that usually becomes more active (compared to a passive baseline) when monitoring behavior. Activity levels were lowest during the least "interesting," or salient, version of the test — when there was no monetary reward and the words shown were neutral household terms. Within the cocaine-user group, activity levels were lowest in the people who had used cocaine most frequently in the 30 days prior to the test.

* The cocaine users also had reduced activity in another part of the anterior cingulate cortex that usually becomes less active (compared to a passive baseline) when someone is successfully suppressing emotional feelings. Within the cocaine-user group, activity levels during the high-salience version of the test — when each fast, correct answer was rewarded with 50 cents and the words presented were drug-related — were lowest in the people who were most successful in suppressing the task-induced craving. In healthy controls, who did not report craving, activation in this region was not significantly different from baseline.

* The functions within the behavior-monitoring and emotion-monitoring brain regions were interconnected in the healthy control subjects but not in the addicted individuals. In all, these group differences in brain function and interconnectivity were quite robust and all the more meaningful in that there were no differences between the groups in performance on or interest ratings for the task.

"When you really have to suppress a powerful negative emotion, like sadness, anxiety or drug craving, activity in this brain region is supposed to decrease, possibly to tune out the background 'noise' of these emotions so you can focus on the task at hand," Goldstein said.

"Our results show that activity in this region indeed went down in the drug-using group, suggesting they were actively trying to suppress craving. Indeed subjects who reported the highest levels of task-induced craving were the least able to suppress activity in this particular brain region.

"This could be because these drug users were still being distracted by background 'noise' stimuli, like memories of having taken drugs or anticipation of further use," Goldstein said.

"This work gives us some clues as to what happens when drug users are unable to suppress craving — and how that might work together with a decreased ability to monitor behavior, even during neutral, non-emotional situations, to make some people more vulnerable to taking drugs," Goldstein said.

The findings point to the importance of improving activity in the behavior-monitoring brain region, possibly by using behavioral and pharmacological approaches to increase motivation and top-down monitoring. Treatments aimed at strengthening activity in the emotion-monitoring brain region may further help addicted individuals regain self-control, especially during hard to suppress highly emotional situations (e.g., during craving). Treatments aimed at strengthening the interconnectivity between these brain regions may decrease impulsivity.

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the General Clinical Research Center of Stony Brook University.

Ultraviolet LEDs Create Darker, Redder Lettuce Richer In Antioxidants

Sunday, May 24, 2009 at 9:06 PM Posted by Sajith

Salad dressing aside, a pile of spinach has more nutritional value than a wedge of iceberg lettuce. That's because darker colors in leafy vegetables are often signs of antioxidants that are thought to have a variety of health benefits. Now a team of plant physiologists has developed a way to make lettuce darker and redder—and therefore healthier—using ultraviolet light-emitting diodes (LEDs).Steven Britz of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Beltsville, Md., and colleagues will present the research at the 2009 Conference on Lasers and Electro Optics/International Quantum Electronics Conference (CLEO/IQEC), which takes place May 31 to June 5 at the Baltimore Convention Center.

The dark red tinges on a leaf of red leaf lettuce are the plant kingdom's equivalent of suntan lotion. When bombarded with ultraviolet rays from the sun, the lettuce leaf creates UV-absorbing polyphenolic compounds in its outer layer of cells. Some of these compounds are red and belong to the same family that gives color to berries and apple skin. They help block ultraviolet radiation, which can mutate plant DNA and damage the photosynthesis that allows a plant to make its food.

Polyphenolic compounds,which include flavonoids like quercetin and cyanidin, are also powerful antioxidants. Diets rich in antioxidants are thought to provide a variety of health benefits to human beings, from improving brain function to slowing the wear and tear of aging.

To create red leaf lettuce plants enriched with these compounds, Britz purchased low-power LEDs that shine with UVB light, a component of natural sunlight. In small quantities, this ultraviolet light allows humans to produce vitamin D, which has been cited for its health benefits. Britz exposed the plants to levels of UVB light comparable to those that a beach goer would feel on a sunny day, approximately 10 milliwatts per square meter.

After 43 hours of exposure to UVB light, the growing lettuce plants were noticeably redder than other plants that only saw white light. Though the team has yet to quantify this effect, it appears to increase as the intensity of the light increases. The effect also seems to be particularly sensitive to the wavelength used – peaking at 282 and 296 nanometers, and absent for longer wavelength UV. "We've been pleasantly surprised to see how effective the LEDs are, and are now testing how much exposure is required, and whether the light should be pulsed or continuous," says Britz.

To cut transportation costs and feed the market in the wintertime, more produce is grown in greenhouses. Crops grown in the winter in northern climes receive very little UVB to begin with, and plants in greenhouses are further shielded from UVB by the glass walls. Ultraviolet LEDs could provide a way to replace and enhance this part of the electromagnetic spectrum to produce darker, more colorful lettuces.

Britz also discussed the potential for using UV LEDs to preserve nutrients in vegetables that have already been harvested. Previous experiments have shown that the peel of a picked apple stays redder for a longer period of time when exposed to ultraviolet light. UVB LEDs are a promising technology for irradiating vegetables stored at low temperatures to maintain or even boost the amount of phytonutrients they contain.

Presentation PTuA3, "Shedding light on nutrition," Steven Britz, June 2.

Fish Really Is 'Brain Food': Vitamin D May Lessen Age-related Cognitive Decline

Friday, May 22, 2009 at 7:25 AM Posted by Sajith

Eating fish – long considered ‘brain food’ – may really be good for the old grey matter, as is a healthy dose of sunshine, new research suggests.University of Manchester scientists in collaboration with colleagues from other European centres have shown that higher levels of vitamin D – primarily synthesised in the skin following sun exposure but also found in certain foods such as oily fish – are associated with improved cognitive function in middle-aged and older men.

The study, published in the Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, compared the cognitive performance of more than 3,000 men aged 40 to 79 years at eight test centres across Europe.

The researchers found that men with higher levels of vitamin D performed consistently better in a simple and sensitive neuropsychological test that assesses an individual’s attention and speed of information processing.

“Previous studies exploring the relationship between vitamin D and cognitive performance in adults have produced inconsistent findings but we observed a significant, independent association between a slower information processing speed and lower levels of vitamin D,” said lead author Dr David Lee, in Manchester’s School of Translational Medicine.

“The main strengths of our study are that it is based on a large population sample and took into account potential interfering factors, such as depression, season and levels of physical activity.

“Interestingly, the association between increased vitamin D and faster information processing was more significant in men aged over 60 years, although the biological reasons for this remain unclear.”

“The positive effects vitamin D appears to have on the brain need to be explored further but certainly raise questions about its potential benefit for minimising ageing-related declines in cognitive performance.”

Face Protection Effective In Preventing The Spread Of Influenza, Study Suggests

at 7:22 AM Posted by Sajith

A new article in the journal Risk Analysis assessed various ways in which aerosol transmission of the flu, a central mode of diffusion which involves breathing droplets in the air, can be reduced. Results show that face protection is a key infection control measure for influenza and can thus affect how people should try to protect themselves from the swine flu.Lawrence M. Wein, Ph.D., and Michael P. Atkinson of Stanford University constructed a mathematical model of aerosol transmission of the flu to explore infection control measures in the home.

Their model predicted that the use of face protection including N95 respirators (these fit tight around the face and are often worn by construction workers) and surgical masks (these fit looser around the face and are often worn by dental hygienists) are effective in preventing the flu. The filters in surgical masks keep out 98 percent of the virus. Also, only 30 percent of the benefits of the respirators and masks are achieved if they are used only after an infected person develops symptoms.

"Our research aids in the understanding of the efficacy of infection control measures for influenza, and provides a framework about the routes of transmission," the authors conclude.

This timely article has the potential to impact current efforts and recommendations to control the so-called swine flu by international, national and local governments in perspective.

This study is published in the journal Risk Analysis. Media wishing to receive a PDF of this article may contact .net.

Bad Breath? New Pocket-sized Breath Test Developed

Wednesday, May 20, 2009 at 7:34 AM Posted by Sajith

A quick breath check in the palm of your hand can never give accurate results. Whether you're about to lean in for a smooch or start a job interview, you're better off asking a trusted friend if your breath is sweet. But what if a friend isn't around when you need one?

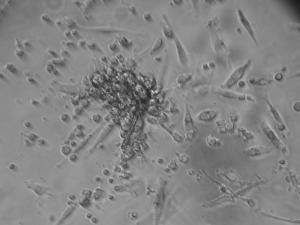

Tel Aviv University researchers have come up with the ultimate solution — a pocket-size breath test which lets you know if malodorous bacteria are brewing in your mouth. A blue result suggests you need a toothbrush. But if it's clear, you're "okay to kiss."

Until now, scientists believed that only one population of bacteria (the Gram-negative ones) break down the proteins in the mouth and produce foul odor. But Prof. Mel Rosenberg and Dr. Nir Sterer of TAU's Sackler Faculty of Medicine recently discovered that the other population of bacteria (the Gram-positive ones) are bad breath's bacterial partner. These bacteria appear to help the Gram-negative ones by producing enzymes that chop sugary bits off the proteins that make them more easily degraded. This enzymatic activity, present in saliva, serves as the basis for the new "OkayToKiss" test.

Prof. Rosenberg, international authority on the diagnosis and treatment of bad breath, who co-developed the kit with Dr. Sterer, published their findings this past March in the Journal of Breath Research, of which Prof. Rosenberg is editor-in-chief. An earlier invention of Prof. Rosenberg led to the development of two-phase mouthwashes that have become a hit in the UK, Israel and elsewhere.

From the Lab to Your Pocket

The patent-pending invention is the result of ongoing research in Prof. Rosenberg's laboratory.

"All a user has to do is dab a little bit of saliva onto a small window of the OkayToKiss kit," explains Prof. Rosenberg: "OkayToKiss will turn blue if a person has enzymes in the mouth produced by the Gram-positive bacteria. The presence of these enzymes means that the mouth is busily producing bacteria that foster nasty breath," he explains.

Apart from its social uses, the test can be used as an indicator of a person's oral hygiene, encouraging better health habits, such as flossing, brushing the teeth, or scheduling that long-delayed visit to the dentist.

OkayToKiss could be ready in about a year for commercial distribution, probably in the size of a pack of chewing gum, to fit in a pocket or purse. It is disposable and could be distributed alongside breath-controlling products.

Science Behind the Smells

"For about 7 years now, we've suspected that there's another kind of bacteria at work in the mouth which causes bad breath," says Prof. Rosenberg. "Now, we are able to grow these bacteria from saliva in an artificial biofilm, showing that there are two distinct populations at work."

In the biofilm — the basis of the new breath test — the color difference between the Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria is remarkable. In the top layer of the biofilm, the bacterium take the glycoproteins in the saliva and chop off sugar residues to produce volatile proteins. On the lower layer in the biofilm, which could roughly be compared to one's tongue or inner lining of the mouth, reside the known and established Gram-negative bacteria.

Biomarkers, like the ones used by Prof. Rosenberg's new invention, are the basis of popular diagnostic kits today, like home pregnancy tests or glucose monitors used by diabetics. Checking the sweetness of one's breath may seem frivolous, but millions worry about it on a continual basis. Prof. Rosenberg's continued research into biomarkers in saliva is very promising for diagnosing other more serious disorders, including indicators for lung cancer, asthma and ulcers.

Prof. Rosenberg has summarized his twenty years of his research and experience on bad breath problems in a new book, Save Your Breath, due out in two months. This new work is a collaborative effort with Dr. Nir Sterer and Dr. Miriam Shaharbany of the Sackler Medical Faculty.

New Way Of Treating The Flu

at 7:30 AM Posted by Sajith

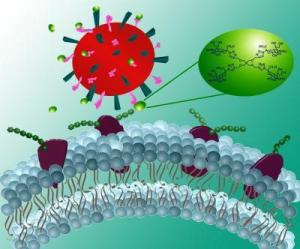

What happens if the next big influenza mutation proves resistant to the available anti-viral drugs? This question is presenting itself right now to scientists and health officials this week at the World Health Assembly in Geneva, Switzerland, as they continue to do battle with H1N1, the so-called swine flu, and prepare for the next iteration of the ever-changing flu virus.Promising new research announced by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute could provide an entirely new tool to combat the flu. The discovery is a one-two punch against the illness that targets the illness on two fronts, going one critical step further than any currently available flu drug.

"We have been fortunate with H1N1 because it has been responding well to available drugs. But if the virus mutates substantially, the currently available drugs might be ineffective because they only target one portion of the virus," said Robert Linhardt, the Ann and John H. Broadbent Jr. '59 Senior Constellation Professor of Biocatalysis and Metabolic Engineering at Rensselaer. "By targeting both portions of the virus, the H and the N, we can interfere with both the initial attachment to the cell that is being infected and the release of the budding virus from the cell that has been affected."

The findings of the team, which have broad implications for future flu drugs, will be featured on the cover of the June edition of European Journal of Organic Chemistry.

The influenza A virus is classified based on the form of two of its outer proteins, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). Each classification – for example H5NI "bird flu" or H1N1 "swine flu" – represents a different mutation of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase or H and N.

Flu drugs currently on the market target only the neuraminidase proteins, and disrupt the ability of the virus to escape an infected cell and move elsewhere to infect other healthy cells. The new process developed by Linhardt is already showing strong binding potential to hemagglutinin, which binds to sialic acid on the surface of a healthy cell, allowing the virus to entire the cell.

"We are seeing promising preliminary results that the chemistry of this approach will be effective in blocking the hemagglutinin portion of the disease that is currently not targeted by any drug on the market," he said.

In addition, Linhardt and his team have shown their compound to be just as effective at targeting neuraminidase as the most popular drugs on the market, according to Linhardt.

The approach can also be modified to specifically target the neuraminidase or the hemagglutinin, or both, depending on the type of mutation that is present in the current version of the flu, according to Linhardt.

In the next steps of his research, Linhardt will look at how their compounds bind to hemagglutinin, and he will test the ability to block the virus first in cell cultures and then in infected animal models.

"It is still early in the process," he said. "We are several steps away from a new drug, but this technique is allowing us to move very quickly in creating and testing these compounds."

The technique that Linhardt used is the increasingly popular technique of "click chemistry." Linhardt is among the first researchers in the world to utilize the technique to create new anti-viral agents. The process allows chemists to join small units of a substance together quickly to create a new, full substance.

In this case, Linhardt used the technique to quickly build a new derivative of sialic acid. Because it is chemically very similar to the sialic acid found on the surface of a cell, the virus could mistake the compound as the real sialic acid and bind to it instead of the cell, eliminating the connections to hemagglutinin and neuraminidase that are required for initial infection and spread of the infection in the body. The currently available drugs are translation-state inhibitors whose chemical structure allows them to only effectively target the neuraminidase.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Linhardt was joined in the research by Michel Weïwer, Chi-Chang Chen, and Melissa Kemp of Rensselaer.

Environmental Exposure To Particulates May Damage DNA In As Few As Three Days

Monday, May 18, 2009 at 6:27 AM Posted by Sajith

Exposure to particulate matter has been recognized as a contributing factor to lung cancer development for some time, but a new study indicates inhalation of certain particulates can actually cause some genes to become reprogrammed, affecting both the development and the outcome of cancers and other diseases.The research will be presented on May 17, at the 105th International Conference of the American Thoracic Society in San Diego.

"Recently, changes in gene programming due to a chemical transformation called methylation have been found in the blood and tissues of lung cancer patients," said investigator Andrea Baccarelli, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of applied biotechnology at the University of Milan. "We aimed at investigating whether exposure to particulate matter induced changes in DNA methylation in blood from healthy subjects who were exposed to high levels of particulate matter in a foundry facility."

Researchers enrolled 63 healthy subjects who worked in a foundry near Milan, Italy. Blood DNA samples were collected on the morning of the first day of the work week, and again after three days of work. Comparing these samples revealed that significant changes had occurred in four genes associated with tumor suppression.

"The changes were detectable after only three days of exposure to particulate matter, indicating that environmental factors need little time to cause gene reprogramming which is potentially associated with disease outcomes," Dr. Baccarelli said.

"As several of the effects of particulate matter in foundries are similar to those found after exposure to ambient air pollution, our results open new hypotheses about how air pollutants modify human health," he added. "The changes in DNA methylation we observed are reversible and some of them are currently being used as targets of cancer drugs."

Dr. Baccarelli said the study results indicate that early interventions might be designed which would reverse gene programming to normal levels, reducing the health risks of exposure.

"We need to evaluate how the changes in gene reprogramming we observed are related to cancer risk," he said. "Down the road, it will be particularly important not only to show that these changes are associated with increased risk of cancer or other environmentally-induced diseases, but that, if we were able to prevent or revert them, these risks could be eliminated."

Session # A45: "Genetic Basis for Environmental and Occupational Respiratory Diseases." Abstract # 2589: "Effects of Particulate Matter Exposure on p16, p53, APC and RASSF1A Promoter Methylation" Poster Board # C51

Gene Key To Alzheimer's-like Reversal Identified: Success In Restoring Memories In Mice Could Lead To Human Treatments

Saturday, May 16, 2009 at 8:14 AM Posted by Sajith

A team led by researchers at MIT's Picower Institute for Learning and Memory has now pinpointed the exact gene responsible for a 2007 breakthrough in which mice with symptoms of Alzheimer's disease regained long-term memories and the ability to learn.In the latest development, reported in the May 7 issue of Nature, Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience, and colleagues found that drugs that work on the gene HDAC2 reverse the effects of Alzheimer's and boost cognitive function in mice.

"This gene and its protein are promising targets for treating memory impairment," Tsai said. "HDAC2 regulates the expression of a plethora of genes implicated in plasticity — the brain's ability to change in response to experience — and memory formation.

"It brings about long-lasting changes in how other genes are expressed, which is probably necessary to increase numbers of synapses and restructure neural circuits, thereby enhancing memory," she said.

The researchers treated mice with Alzheimer's-like symptoms using histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors. HDACs are a family of 11 enzymes that seem to act as master regulators of gene expression. Drugs that inhibit HDACs are in experimental stages and are not available by prescription for use for Alzheimer's.

"Harnessing the therapeutic potential of HDAC inhibitors requires knowledge of the specific HDAC family member or members linked to cognitive enhancement," Tsai said. "We have now identified HDAC2 as the most likely target of the HDAC inhibitors that facilitate synaptic plasticity and memory formation.

"This will help elucidate the mechanisms by which chromatin remodeling regulates memory," she said. It also will shed light on the role of epigenetic regulation, through which gene expression is indirectly influenced, in physiological and pathological conditions in the central nervous system.

"Furthermore, this finding will lead to the development of more selective HDAC inhibitors for memory enhancement," she said. "This is exciting because more potent and safe drugs can be developed to treat Alzheimer's and other cognition diseases by targeting this HDAC specifically," said Tsai, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Several HDAC inhibitors are currently in clinical trials as novel anticancer agents and may enter the pipeline for other diseases in the coming two to four years. Researchers have had promising results with HDAC inhibitors in mouse models of Huntington's disease.

Remodeling structures

Proteins called histones act as spools around which DNA winds, forming a structure in the cell nucleus known as chromatin. Histones are modified in various ways, including through a process called acetylation, which in turn modifies chromatin shape and structure. (Inhibiting deacetylation with HDAC inhibitors leads to increased acetylation.)

Certain HDAC inhibitors open up chromatin. This allows transcription and expression of genes in what had been a too tightly packaged chromatin structure in which certain genes do not get transcribed.

There has been exponential growth in HDAC research over the past decade. HDAC inhibitors are currently being tested in preclinical studies to treat Huntington's disease. Some HDAC inhibitors are on the market to treat certain forms of cancer. They may help chemotherapy drugs better reach their targets by opening up chromatin and exposing DNA. "To our knowledge, HDAC inhibitors have not been used to treat Alzheimer's disease or dementia," Tsai said. "But now that we know that inhibiting HDAC2 has the potential to boost synaptic plasticity, synapse formation and memory formation, in the next step, we will develop new HDAC2-selective inhibitors and test their function for human diseases associated with memory impairment to treat neurodegenerative diseases."

The researchers conducted learning and memory tasks using transgenic mice that were induced to lose a significant number of brain cells. Following Alzheimer's-like brain atrophy, the mice acted as though they did not remember tasks they had previously learned.

But after taking HDAC inhibitors, the mice regained their long-term memories and ability to learn new tasks. In addition, mice genetically engineered to produce no HDAC2 at all exhibited enhanced memory formation.

The fact that long-term memories can be recovered by elevated histone acetylation supports the idea that apparent memory "loss" is really a reflection of inaccessible memories, Tsai said. "These findings are in line with a phenomenon known as 'fluctuating memories,' in which demented patients experience temporary periods of apparent clarity," she said.

In addition to Tsai, co-authors are Picower postdoctoral associate Ji-Song Guan; and colleagues from Massachusetts General Hospital; Harvard Medical School; the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research; MIT's Department of Biology; the Dana Farber Cancer Institute; and the Netherlands Cancer Institute.

This work is supported by the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Stanley Center for Psychiatric research at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT; the NARSAD, a mental health foundation, the National Cancer Institute, the Damon-Runyon Cancer Research Foundation; the Dutch Cancer Society; the National Institutes of Health; and the Robert A. and Renee E. Belfer Institute for Applied Cancer Science.

Ginger Quells Cancer Patients' Nausea From Chemotherapy

at 8:10 AM Posted by Sajith

People with cancer can reduce post-chemotherapy nausea by 40 percent by using ginger supplements, along with standard anti-vomiting drugs, before undergoing treatment, according to scientists at the University of Rochester Medical Center.About 70 percent of cancer patients who receive chemotherapy complain of nausea and vomiting. "There are effective drugs to control vomiting, but the nausea is often worse because it lingers," said lead author Julie L. Ryan, Ph.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of Dermatology and Radiation Oncology at Rochester's James P. Wilmot Cancer Center. The research will be presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting in the Patient and Survivor Care Session on Saturday, May 30, in Orlando, Fla.

"Nausea is a major problem for people who undergo chemotherapy and it's been a challenge for scientists and doctors to understand how to control it," said Ryan, a member of Rochester's Community Clinical Oncology Program Research Base at the Wilmot Cancer Center. Her research is the largest randomized study to demonstrate the effectiveness of ginger supplements to ease the nausea. Previous small studies have been inconsistent and never focused on taking the common spice before chemotherapy.

The Phase II/III placebo-controlled, double-blind study included 644 cancer patients who would receive at least three chemotherapy treatments. They were divided into four arms that received placebos, 0.5 gram of ginger, 1 gram of ginger, or 1.5 grams of ginger along with antiemetics (anti-vomiting drugs such as Zofran®, Kytril®, Novaban®, and Anzemet®.)

Patients took the ginger supplements three days prior to chemotherapy and three days following treatment. Patients reported nausea levels at various times of day during following their chemotherapy and those who took the lower doses had a 40 percent reduction.

Ginger is readily absorbed in the body and has long been considered a remedy for stomach aches. "By taking the ginger prior to chemotherapy treatment, the National Cancer Institute-funded study suggests its earlier absorption into the body may have anti-inflammatory properties," Ryan said.

Rochester's Community Clinical Oncology Program Research Base is a national cooperative research group funded by the National Cancer Institute. The Wilmot Cancer Center team specializes in improving the quality of life of people who have cancer.

African Tea Offers Promising Treatment For Type-2 Diabetes

Monday, May 11, 2009 at 5:44 AM Posted by Sajith

Researchers are attempting, with the help of a special African tea, to develop a new treatment for type-2 diabetics. The tea is used as a treatment in traditional Nigerian medicine and is produced from the extract of Rauvolfia Vomitoria leaves and the fruit of Citrus aurantium. The scientists have recently tested the tea on patients with type-2 diabetes and the results are promising.The researchers have harvested the ingredients for the tea in Africa, totalling approximately fifty kilos of leaves and three hundred kilos of fruit from the wild nature of Nigeria. Afterwards the tea has been produced exactly as local healers would do so. The recipe is quite simple: boil the leaves, young stalks and fruit and filter the liquid.

First mice, then humans

Associate professor Per Mølgaard and postdoc Joan Campbell-Tofte from the Department of Medicinal Chemistry have previously tested the tea on genetically diabetic mice. The results of the tests showed that after six weeks of daily treatment with the African tea, combined with a low-fat diet, resulted in changes in the combination and amount of fat in the animals' eyes and protection of the fragile pancreas of the mice.

The researchers have recently completed a four month long clinical test on 23 patients with type-2 diabetes and are more than satisfied with the result.

"The research subjects drank 750ml of tea each day. The [tea] appears to differentiate itself from other current type-2 diabetes treatments because the tea does not initially affect the sugar content of the blood. But after four months of treatment with tea we can, however, see a significant increase in glucose tolerance," said postdoc Joan Campbell-Tofte from the University of Copenhagen.

Changes in fatty acid composition

The clinical tests show another pattern in the changes in fatty acid composition with the patients treated in comparison with the placebo group.

"In the patient group who drank the tea, the number of polyunsaturated fatty acids increased. That is good for the body's cells because the polyunsaturated fat causes the cell membranes to be more permeable, which results in the cells absorbing glucose better from the blood," said Joan Campbell-Tofte.

The researchers hope that new clinical tests and scientific experiments in the future will result in a new treatment for type-2 diabetics.

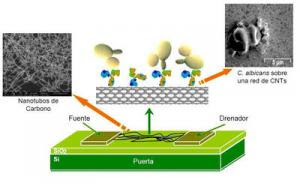

Sexually Transmitted Infections: Transistors Used To Detect Fungus Candida Albicans

at 5:39 AM Posted by Sajith

The Nanosensors group from the Universidad Rovira i Virgili has created a biosensor, an electrical and biological device, which is able to selectively detect the Candida albicans yeast in very small quantities of only 50 cfu/ml (colony-forming units per millilitre)."The technique uses field-effect transistors (electronic devices that contain an electrode source and a draining electrode connected to a transducer) based on carbon nanotubes and with Candida albicans-specific antibodies", Raquel A. Villamizar, lead author of the study said.

The Candida samples, which can be obtained from blood, serum or vaginal secretions, are placed directly on the biosensor, where the interaction between antigens and antibodies changes the electric current of the devices. This change is recorded and makes it possible to measure the amount of yeast present in a sample.

"Thanks to the extraordinary charge transference properties of the carbon nanotubes, the fungus detection process is direct, fast, and does not require the use of any marker", remarks Villamizar, who is co-author of a study that provides details of the biosensor and was published recently in the journal Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical.

To date, conventional diagnosis of Candida has been carried out using microbial cultures, serological tests, PCR molecular biology techniques (polymerase chain reactions used to amplify DNA), or immunoassays such as ELISA (Enzyme Linked Inmunoabsorbent Assay).

These techniques require long analysis times and sometimes give rise to false positives and negatives. ELISA also requires the use of markers (compounds that must be added to detect the presence of yeast by fluorescence and other techniques).

The new carbon nanotubes biosensor, however, "makes it possible to improve some of the quality parameters of the traditional methods, for example the speed and simplicity of measurements, and it is an alternative tool that could be used in routine sample analysis", explains Villamizar.

The researcher adds that by using this biosensor "it will be possible in future to obtain a rapid diagnosis of infection with this pathogen, which will help to ensure administration of the correct prophylactic treatments".

The Candida albicans fungus exists naturally in the skin, mouth, the mucous membranes lining the digestive tract, and the respiratory and genitourinary systems. This yeast can cause anything from simple mycosis of the skin to complicated cases of candidiasis. It is much more commonly found in patients suffering from immunodeficiency, tumours, diabetes and lymphomas, among other diseases.

Search

Labels

- Alzheimer's (10)

- Antibiotics (7)

- Anxiety (1)

- articles (2)

- Bacteria (1)

- behavioral abnormality (1)

- Bio technology (1)

- Brain (8)

- breast cancer (6)

- Cancer (40)

- cancer treatment (7)

- chemotherapy (6)

- Chlamydia (1)

- Cytology (3)

- Death (1)

- Diabetes Mellitus (7)

- Diet (17)

- DNA (1)

- Doctors (1)

- epilepsy (2)

- Fossil (1)

- fruits (1)

- genes (6)

- Genetics (13)

- Geriatrics (1)

- Health (12)

- Heart diseases (9)

- Herbal Medicine (2)

- HIV and AIDS (7)

- influenza (1)

- Inventions (1)

- IVF (1)

- latest findings (1)

- Life style (2)

- Lung Cancer (1)

- Lung Disease (9)

- Microbiology (1)

- Multiple Sclerosis (1)

- Nanotechnology (3)

- Neonatology (1)

- neurology (1)

- News (18)

- Parkinsonism (2)

- Prevention (1)

- Primates (1)

- Prostate cancer (1)

- Prosthetics (1)

- seizure (2)

- Skin (1)

- STD (2)

- Stem cells (9)

- Stroke (1)

- Surgery (2)

- Swine flu (11)

- Virus (1)

- weight loss (1)

Search The Web

Blog Archive

Minyx v2.0 template es un theme creado por Spiga. | Minyx Blogger Template distributed by eBlog Templates