According to the World Health Organization, approximately two billion people suffer from iron deficiency. They tire easily, experience problems in metabolizing harmful substances in their bodies and eventually suffer from anemia. Women and children are particularly affected in developing countries, where rice is the major staple food. Peeled rice, also called polished rice, does not have enough iron to satisfy the daily requirement, even if consumed in large quantities. For many people, a balanced diet or iron supplements are often unaffordable.Rice actually has a lot of iron, but only in the seed coat. Because unpeeled rice quickly becomes rancid in tropical and subtropical climates, however, the seed coat - along with the precious iron - has to be removed for storage. Researchers working with Christof Sautter and Wilhelm Gruissem in the laboratory of plant biotechnology at ETH Zurich have now succeeded in increasing the iron content in polished rice by transferring two plant genes into an existing rice variety. Their work was published July 21 in the online edition of Plant Biotechnology Journal.

Genes help to mobilize and store iron

The rice plants express the two genes to produce the enzyme nicotianamin syn-thase, which mobilizes iron, and the protein ferritin, which stores iron. Their synergistic action allows the rice plant to absorb more iron from the soil and store it in the rice kernel. The product of nicotianamine synthase, called nicotianamin, binds the iron temporarily and facilitates its transportation in the plant. Ferritin acts as a storage depot for iron in both plants and humans. The researchers controlled the genes introduced in such a way that nicotianamin synthase is expressed throughout the rice plant, but ferritin only in the rice kernel. Together, the expression of the genes has a positive impact on iron accumulation in the rice kernel and increases the iron content more than six-fold compared to the original variety.

No negative impacts anticipated

The ETH scientists are excited about the new rice variety. The prototypes behave normally in the greenhouse and show no signs of possible negative effects. "Next we will have to test whether the rice plants also perform well in the field under agronomical conditions", says Wilhelm Gruissem. The ETH Professor does not expect the plants to have a negative impact on the environment. It is unlikely that they will deplete the soil of iron, as iron is the most abundant metallic element in it.

Distribution to farmers still many years away

The rice plants will have to undergo many greenhouse and field tests for bio-safety and agronomic performance before the high-iron rice varieties eventually become available to farmers. The current prototypes are unsuitable for agricultural production yet. Although the new rice variety already has an iron content that is nutritionally relevant, Gruissem wants to increase it further. After all, many people who suffer from iron deficiency can only afford one meal per day. If the scientists manage to increase iron in the rice kernel up to twelve-fold, one rice meal will be sufficient to satisfy the daily iron requirement.

The experience with the high-vitamin A "Golden Rice", which was developed at ETH Zurich in collaboration with researchers at the University of Freiburg (Germany), has shown that it takes years before genetically engineered rice can actually be planted by farmers. The regulatory hurdles and costs involved in making genetically modified plants available to agriculture and consumers are very high. The ETH scientists aim to make their high-iron rice plants available to small-scale and self-sufficient farmers free of charge.

INTERNAL MEDICINE The internal medicine blog , where you can have details on alternatice medicine , latest trends in medicine , new drugs in the market , school of medicine etc

Combating Iron Deficiency: Rice With Six Times More Iron Than Polished Rice Kernels Developed

Tuesday, July 21, 2009 at 9:23 PM Posted by Sajith

Green Tea: Mixed Reviews For Cancer Prevention

at 7:12 AM Posted by Sajith

Lifestyle choices are pieces of the cancer prevention puzzle, but exactly which steps to take remain unclear, even to scientists. Still, more and more individuals are incorporating small changes into their daily routine — such as drinking green tea — in hopes of keeping cancer risk at bay.Is it working? A large new Cochrane review of studies that examined the affect of green tea on cancer prevention has yielded conflicting results.

Researchers looked at 51 medium- to high-quality studies that included more than 1.6 million participants. The studies focused on the relationship between green tea consumption and a variety of cancers, including breast, lung, digestive tract, urological prostate, gynecological and oral cancers.

The comprehensive review analyzed studies conducted from 1985 through 2008. Many of the reviewed studies took place in Asia, where tea drinking is widespread and part of the daily routine for many.

The review appears in a recent issue of The Cochrane Library, which is a publication of The Cochrane Collaboration, an international organization that evaluates medical research. Systematic reviews draw evidence-based conclusions about medical practice after considering both the content and quality of existing medical trials on a topic.

“Despite the large number of included studies the jury still seems to be out on the question of whether green tea can in fact prevent the development of various cancer types,” said lead review author Katja Boehm, Ph.D. Since people drink varying amounts of green tea, and different types of cancers vary in how they grow, it is impossible to state definitively that green tea is “good” for cancer prevention.

“One thing is certain…green tea consumption can never account for cancer prevention alone,” said Boehm, a member of the Unconventional and Complementary Methods in Oncology Study Group in Nuremburg, Germany.

Three types of tea — black, green and oolong — come from the plant Camellia sinensis, and all contain polyphenols. Catechins, a subgroup of the polyphenols, are powerful antioxidants. Some say the polyphenols in green tea are unique, preventing cell growth and thus having the potential to prevent cancer.

The review found that green tea had limited benefits for liver cancer, but found conflicting evidence for other gastrointestinal cancers, such as cancer of the esophagus, colon or pancreas. One study found a decreased risk of prostate cancer for men who consumed higher quantities of green tea or its extracts.

The review did not find any benefit for preventing death from gastric cancer, and found that green tea might even increase the risk of urinary bladder cancer. Despite conflicting findings, there was “limited moderate to strong evidence” of a benefit for lung, pancreatic and colorectal cancer. None of the studies that simply observed a group of people over time found a benefit for breast cancer prevention. However, both of the case control studies — which compare people without a condition to people with it — found a positive association between green tea consumption and a decreased risk of breast cancer.

Nagi Kumar, Ph.D., director of Nutrition Research at Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla., is optimistic about the potential for green tea in cancer prevention. “The substances found in green tea are certainly promising,” Kumar said. “The field now has progressed to where we [can]…test the effectiveness and safety of green tea polyphenols using a drug form similar to the constituents in tea to see if we can prevent cancer progression. Time will tell.”

Kumar said the Cochrane review was “more an inventory of studies completed rather than a systematic scientific review,” adding that “the discussion lacks a scientific approach in the interpretation of the discordant findings.”

Kumar also noted that several groups are conducting randomized clinical trials, including one comprising six institutions: the Moffitt Cancer Center and the James A Haley VA Medical Center, University of Chicago, Jefferson in Philadelphia, University of Florida and Louisiana State University.

Both scientists agreed that more research is a good idea. Boehm said she highly recommends the conduction of a large, well-designed, study with adequate green tea consumption levels.

“The review provides where we have been in this field of research and where we are going and how much more we have on hand,” Kumar said. “Although not as thorough as I would like it, it is a good quality review.”

Therefore, while the questions about green tea consumption and cancer prevention remain unanswered, one thing remains clear: It is fine to consume green tea if you enjoy it and it might prove beneficial in the over time.

“If not exceeding the daily recommended allowance those who enjoy a cup of green tea should continue its consumption,” Boehm said. “Drinking green tea appears to be safe at regular, habitual and moderate use at its recommended dosage of up to 1200 ml/day.” That comes to a little over five cups a day.

Handle With Care: Telomeres Resemble DNA Fragile Sites

Friday, July 17, 2009 at 6:34 AM Posted by Sajith

Telomeres, the repetitive sequences of DNA at the ends of linear chromosomes, have an important function: They protect vulnerable chromosome ends from molecular attack. Researchers at Rockefeller University now show that telomeres have their own weakness. They resemble unstable parts of the genome called fragile sites where DNA replication can stall and go awry. But what keeps our fragile telomeres from falling apart is a protein that ensures the smooth progression of DNA replication to the end of a chromosome.The research, led by Titia de Lange, head of the Laboratory of Cell Biology and Genetics, and first author Agnel Sfeir, a postdoctoral associate in the lab, suggests a striking similarity between telomeres and common fragile sites, parts of the genome where breaks tend to occur, albeit infrequently. (Humans have 80 common fragile sites, many of which have been linked to cancer.) De Lange and Sfeir found that these newly discovered fragile sites make it difficult for DNA replication to proceed, a discovery that unveils a new replication problem posed by telomeres.

At the center of the discovery is a protein known as TRF1, which de Lange, in an effort to understand how telomeres protect chromosome ends, discovered in 1995. Using a conditional mouse knockout, de Lange and Sfeir have now revealed that TRF1, which is part of a six-protein complex called shelterin, enables DNA replication to drive smoothly through telomeres with the aid of two other proteins.

“Telomeric DNA has a repetitive sequence that can form unusual DNA structures when the DNA is unwound during DNA replication,” says de Lange. “Our data suggest that TRF1 brings in two proteins that can take out these structures in the telomeric DNA. In other words, TRF1 and its helpers remove the bumps in the road so that the replication fork can drive through.”

The work, published in the July 10 issue of Cell, began when Sfeir deleted TRF1 and saw that the telomeres resembled common fragile sites, suggesting that TRF1 protects telomeres from becoming fragile. Instead of a continuous string of DNA, the telomeres were broken into fragments of twos and threes. To see if the replication fork stalls at telomeres, de Lange and Sfeir joined forces with Carl L. Schildkraut, a researcher at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. Using a technique called SMARD, the researchers observed the dynamics of replication across individual DNA molecules — the first time this technique has been used to study telomeres. In the absence of TRF1, the fork often stalled for a considerable amount of time.

The only other known replication problem posed by telomeres was solved in 1985 when it was shown that the enzyme telomerase elongates telomeres, which shorten during every cell division. The second problem posed by telomeres, the so-called end-protection problem, was solved by de Lange and her colleagues when they found that shelterin protects the ends of linear chromosomes, which look like damaged DNA, from unnecessary repair. Working with TRF1, the very first shelterin protein ever to be identified, de Lange and Sfeir have not only unveiled a completely unanticipated replication problem at telomeres, they have also shown how it is solved.

The research lays new groundwork for the study of common fragile sites throughout the genome, explains de Lange. “Fragile sites have always been hard to study because no specific DNA sequence preceeds or follows them,” she says. “In constrast, telomeres represent fragile sites with a known sequence, which may help us understand how common fragile sites break throughout the genome — and why.”

HIV-related Death: Predicting Fatal Fungal Infections

Saturday, July 4, 2009 at 4:22 AM Posted by Sajith

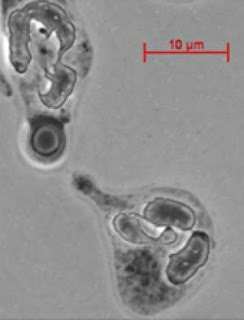

In a study published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases, researchers from Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University have identified cells in blood that predict which HIV-positive individuals are most likely to develop deadly fungal meningitis, a major cause of HIV-related death. This form of meningitis affects more than 900,000 HIV-infected people globally—most of them in sub-Saharan Africa and other areas of the world where antiretroviral therapy for HIV is not available.A major cause of fungal meningitis is Cryptococcus neoformans, a yeast-like fungus commonly found in soil and in bird droppings. Virtually everyone has been infected with Cryptococcus neoformans, but a healthy immune system keeps the infection from ever causing disease.

The risk of developing fungal meningitis from Cryptococcus neoformans rises dramatically when people have weakened immunity, due to HIV infection or other reasons including the use of immunosuppressive drugs after organ transplantation, or for treating autoimmune diseases or cancer. Knowing which patients are most likely to develop fungal meningitis would allow costly drugs for preventing fungal disease to be targeted to those most in need. (In the U.S., the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy by HIV-infected people, and their preventive use of anti-fungal drugs, has dramatically reduced their rate of fungal meningitis from Cryptococcus neoformans to about 2%.)

In this study, Liise-anne Pirofski, M.D., describes a technique for predicting which HIV-infected patients are at greatest risk for developing fungal meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans. Dr. Pirofski is chief in the division of infectious diseases at Einstein.

Dr. Pirofski and her colleagues counted the number of immune cells known as IgM memory B cells in the bloodstream of three groups of individuals: people infected with HIV who had a history of fungal meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans; people infected with HIV but with no history of the disease; and those with no history of either HIV infection or the disease.

"We were astounded to find a profound difference in the level of these IgM memory B cells between the HIV-infected groups," said Dr. Pirofski. "The HIV-infected people with fungal meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans had much lower levels of these cells."

The research team wanted to know if the lower levels of IgM memory B cells in certain HIV-infected individuals resulted from the fungal disease, or whether their reduced levels of these cells preceded their development of the disease.

To find out, Dr. Pirofski analyzed frozen blood samples taken from HIV-infected patients before they had developed fungal meningitis due to Cryptococcus neoformans. Years before these HIV-infected patients were diagnosed with meningitis, their blood had far fewer IgM memory B cells than HIV-infected patients who didn't come down with the disease. This suggests that some people are predisposed to develop fungal meningitis because they have low levels of IgM memory B cells that may be due to their genetic makeup.

These findings could be important for many other immunocompromised patients in addition to those infected with HIV. "We think that knowing whether transplant recipients or other patients taking immunosuppressive drugs have low numbers of IgM memory B cells could be useful in deciding which patients should receive antifungal drugs to prevent meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans," says Dr. Pirofski.

Krishanthi Subramanian, Ph.D., who did her thesis work in Dr. Pirofski's laboratory, is the first author of the study.

Police Work Undermines Cardiovascular Health, Comparison To General Population Shows

at 4:16 AM Posted by Sajith

It is well documented that police officers have a higher risk of developing heart disease: The question is why.In the most recent results coming out of one of the few long-term studies being conducted within this tightly knit society, University at Buffalo researchers have determined that underlying the higher incidence of subclinical atherosclerosis -- arterial thickening that precedes a heart attack or stroke -- may be the stress of police work.

"We took lifestyle factors that generally are associated with atherosclerosis, such as exercise, smoking, diet, etc., into account in our comparison between citizens and the police officers," said John Violanti, Ph.D., UB associate professor of social and preventive medicine, who has been studying the police force in Buffalo, N.Y., for 10 years.

"These lifestyle factors were statistically controlled for in the analysis. This led to the conclusion that it is not the 'usual' heart-disease-related risk factors that increase the risk in police officers. It is something else. We believe that 'something else' is the occupation of policing."

Results of the study appear in the June issue of the Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine.

Violanti and colleagues have been studying the role of cortisol, known as the "stress hormone," in these police officers to determine if stress is associated with physiological risk factors that can lead to serious health problems such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

In a study accepted for publication in Psychiatry Research that looked at the male-female differences in stress and signs of heart disease, Violanti found that female police officers had higher levels of cortisol when they awoke, and the levels remained high throughout the day. Cortisol normally is highest in the morning and decreases to its lowest point in the evening. The constantly high cortisol levels were associated with less arterial elasticity, a risk factor for heart disease, Violanti noted.

"When cortisol becomes dysregulated due to chronic stress, it opens a person to disease," he said. "The body becomes physiologically unbalanced, organs are attacked and the immune system is compromised as well. It's unfortunate, but that's what stress does to us."

In the current study, the researchers used carotid artery thickness to assess heart disease risk. Participants were 322 clinically healthy active-duty police officers from the Buffalo Cardio-Metabolic Occupational Police Stress (BCOPS) study and 318 healthy persons from the ongoing UB Western New York Health Study matched to the officers by age.

All measurements were taken in the morning after a 12-hour fast. In addition to testing carotid thickness via ultrasound, investigators measured blood pressure, body size, cholesterol (both total and HDL) and glucose. They collected information on physical activity, symptoms of depression, alcohol consumption and smoking history. These are the factors that typically cause heart disease.

Results showed that police work was associated with increased subclinical cardiovascular disease -- there was more plaque build-up in the carotid artery -- compared to the general population that could not be explained by those conventional heart disease risk factors.

Subclinical atherosclerosis means that the disease shows progression but does not qualify yet as overt heart disease.

"In this case we examined the thickness of the carotid artery as an indicator of increasing risk for atherosclerosis," noted Violanti. "The plaque buildup was greater in police than the citizen population.

"In future work, we will measure the carotid artery thickness again to see how much it has increased. At some point in time, the thickness may reach a stage of possible blockage, which will require medical intervention and treatment. We think that police officers will likely reach that stage quicker than the general population."

P. Nedra Joseph, Ph.D., a former postdoctoral researcher at UB, now at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), is first author on the study. Additional contributors to the study were: from UB -- Richard Donahue, Ph.D., and Joan Dorn, Ph.D., from the UB School of Public Health and Health Professions; Michael E. Andrew, Ph.D., and Cecil M. Burchfiel, from the CDC; and Maurizio Trevisan, M.D., formerly of UB, now head of the University of Nevada Health Sciences System.

The BCOPS study is funded by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Search

Labels

- Alzheimer's (10)

- Antibiotics (7)

- Anxiety (1)

- articles (2)

- Bacteria (1)

- behavioral abnormality (1)

- Bio technology (1)

- Brain (8)

- breast cancer (6)

- Cancer (40)

- cancer treatment (7)

- chemotherapy (6)

- Chlamydia (1)

- Cytology (3)

- Death (1)

- Diabetes Mellitus (7)

- Diet (17)

- DNA (1)

- Doctors (1)

- epilepsy (2)

- Fossil (1)

- fruits (1)

- genes (6)

- Genetics (13)

- Geriatrics (1)

- Health (12)

- Heart diseases (9)

- Herbal Medicine (2)

- HIV and AIDS (7)

- influenza (1)

- Inventions (1)

- IVF (1)

- latest findings (1)

- Life style (2)

- Lung Cancer (1)

- Lung Disease (9)

- Microbiology (1)

- Multiple Sclerosis (1)

- Nanotechnology (3)

- Neonatology (1)

- neurology (1)

- News (18)

- Parkinsonism (2)

- Prevention (1)

- Primates (1)

- Prostate cancer (1)

- Prosthetics (1)

- seizure (2)

- Skin (1)

- STD (2)

- Stem cells (9)

- Stroke (1)

- Surgery (2)

- Swine flu (11)

- Virus (1)

- weight loss (1)

Search The Web

Blog Archive

Minyx v2.0 template es un theme creado por Spiga. | Minyx Blogger Template distributed by eBlog Templates